The Dictatorship

Let us give thanks for democracy as well this Thanksgiving

In 1744, leaders of the Iroquois Confederacy met with representatives of several British colonies to negotiate a treaty. One of the Native Americans, an Onondaga diplomat named Canassatego, pointed out that the colonies could learn from their alliance, which dated back hundreds of years.

“Our wise Forefathers established Union and Amity between the Five Nations; this has made us formidable, this has given us great weight and Authority with our Neighboring Nations,” he said. “We are a powerful confederacy, and, by your observing the same Methods our wise Forefathers have taken, you will acquire fresh Strength and Power.”

The speech was included in a collection printed by Benjamin Franklin, who later mused in a 1751 letter to a friend that it would be “a very strange Thing” if the six nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee, were able to form a union and not “ten or a Dozen English Colonies.”

These are some of the facts cited by supporters of the Iroquois influence theory, which holds that the Native American alliance was an inspiration for the U.S. Constitution. Its adherents further point to similarities in everything from federalism and the impeachment process to the use of the bald eagle and a bundle of arrows as symbols.

Within the field of history, this theory is a subject of some dispute. Historians have picked apart various pieces of evidence and claims about the specific influences that the Iroquois may have had on the delegates to the constitutional convention. And to be fair, some of the scholarship put forward for the Iroquois influence over the years has been overstated or thinly sourcedthough no one would argue that the framers were not aware of the Iroquois example.

The Europeans who came to North America were from countries that had largely run into an authoritarian dead end.

As Kirke Kickingbird, co-author of “Indians and the United States Constitution,” once saidimagining that the framers weren’t influenced by Native Americans would be like saying the Germans and the French didn’t know each other. That influence is worth contemplating on Thanksgiving, a day that acknowledges the debt that all Americans owe to the people who were here first.

The Europeans who came to North America were from countries that had largely run into an authoritarian dead end, overseen by rulers with absolute powers to dictate how their subjects lived and died. Here, the European settlers discovered a vast array of alternatives, including hereditary rulers, ones chosen only after careful debate, leaders who governed by consensus as well as those whose powers were limited to the hunting season or by a tribal council.

Even those Europeans who wanted to defend their system had to grapple with the existence of these alternatives in America in philosophical treatises that in turn influenced American democracy.

Many responded by inaccurately casting Native Americans as living in a sort of anarchy, a “state of nature” that, they implied or outright declared, European society had outgrown. English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose “Leviathan” defends the absolute powers of a king, described the lives of such unfortunates as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” as they lacked the supposed comforts of an all-powerful ruler.

But reformers, too, were preoccupied with America. As he outlined his objections to the divine right of kings in his “Two Treatises of Government,” the English philosopher John Locke described life before the invention of private property by comparing it to the New World. “In the beginning,” he wrote, “all the world was America.” Other Enlightenment thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Montesquieu also wrote about the state of nature in ways that made it clear they were thinking about America, too.

There are plenty of differences, of course, between the Iroquois Confederacy and the U.S. Constitution. The framers of Constitution were also influenced by European sources as varied as ancient Greece, the Roman Republic, the Hanseatic League and Swiss cantons. And the Enlightenment was driven by the spread of coffeehouses and libraries and the rise of a middle-class merchant class, among other things. But to acknowledge all these influences does not mean rejecting the notion that Native Americans were also in the mix.

The encounter between Europeans and Native Americans that began in the 15th century changed both forever profoundly, in ways both good and bad. The introduction of the horse allowed the Plains Indians to flourish, while diseases like smallpox wiped out entire tribes. Europeans picked up new staple crops like potatoes and tomatoes as well as an addiction to tobacco. Sequoyah was inspired to create the Cherokee written language, while European military strategists were influenced by Native American battlefield tactics.

It’s clear that this also included an exchange of ideas on how people should be governed and the proper limits of power that we are still grappling with today. So as we give thanks for the turkey and the corn this Thanksgiving, let us also take a moment to appreciate the gift of these ideas as well.

Ryan Teague Beckwith is a newsletter editor for BLN. He has previously worked for such outlets as Time magazine, Bloomberg News and CQ Roll Call. He teaches journalism at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies.

The Dictatorship

The Supreme Court’s conservative majority eyes more power for the president

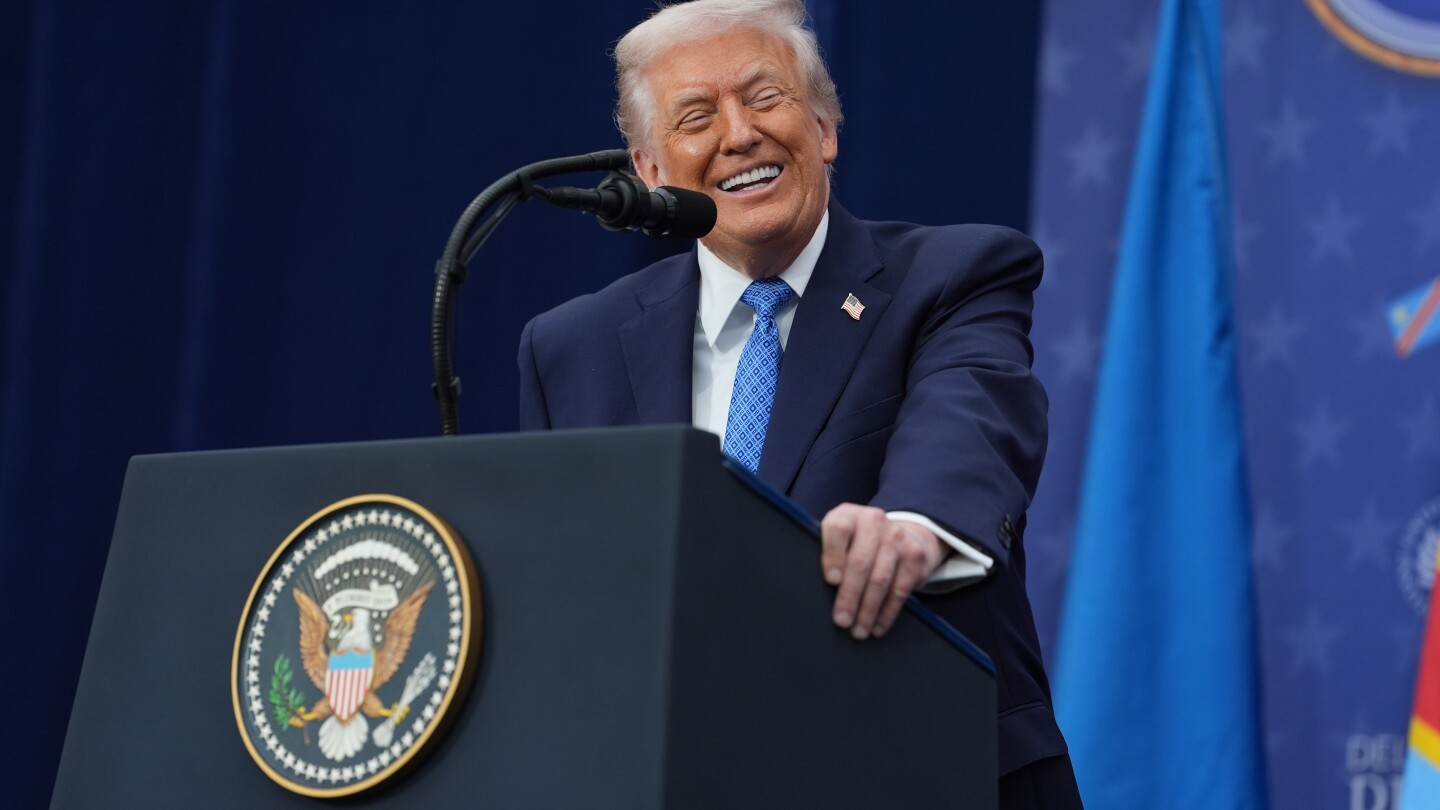

WASHINGTON (AP) — Chief Justice John Roberts has led the Supreme Court ‘s conservative majority on a steady march of increasing the power of the presidency, starting well before Donald Trump’s time in the White House.

The justices could take the next step in a case being argued Monday that calls for a unanimous 90-year-old decision limiting executive authority to be overturned.

The court’s conservatives, liberal Justice Elena Kagan noted in September, seem to be “raring to take that action.”

They already have allowed Trump, in the opening months of the Republican’s second term, to fire almost everyone he has wanted, despite the court’s 1935 decision in Humphrey’s Executor that prohibits the president from removing the heads of independent agencies without cause.

The officials include Rebecca Slaughterwhose firing from the Federal Trade Commission is at issue in the current case, as well as officials from the National Labor Relations Board, the Merit Systems Protection Board and the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

The only officials who have so far survived efforts to remove them are Lisa Cooka Federal Reserve governor, and Shira Perlmuttera copyright official with the Library of Congress. The court already has suggested that it will view the Fed differently from other independent agencies, and Trump has said he wants her out because of allegations of mortgage fraud. Cook says she did nothing wrong.

Humphrey’s Executor has long been a target of the conservative legal movement that has embraced an expansive view of presidential power known as the unitary executive.

The case before the high court involves the same agency, the FTC, that was at issue in 1935. The justices established that presidents — Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt at the time — could not fire the appointed leaders of the alphabet soup of federal agencies without cause.

The decision ushered in an era of powerful independent federal agencies charged with regulating labor relations, employment discrimination, the air waves and much else.

Proponents of the unitary executive theory have said the modern administrative state gets the Constitution all wrong: Federal agencies that are part of the executive branch answer to the president, and that includes the ability to fire their leaders at will.

As Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in a 1988 dissent that has taken on mythical status among conservatives, “this does not mean some of the executive power, but all of the executive power.”

Since 2010 and under Roberts’ leadership, the Supreme Court has steadily whittled away at laws restricting the president’s ability to fire people.

In 2020, Roberts wrote for the court that “the President’s removal power is the rule, not the exception” in a decision upholding Trump’s firing of the head of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau despite job protections similar to those upheld in Humphrey’s case.

In the 2024 immunity decision that spared Trump from being prosecuted for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election results, Roberts included the power to fire among the president’s “conclusive and preclusive” powers that Congress lacks the authority to restrict.

But according to legal historians and even a prominent proponent of the originalism approach to interpreting the Constitution that is favored by conservatives, Roberts may be wrong about the history underpinning the unitary executive.

“Both the text and the history of Article II are far more equivocal than the current Court has been suggesting,” wrote Caleb Nelson, a University of Virginia law professor who once served as a law clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas.

Jane Manners, a Fordham University law professor, said she and other historians filed briefs with the court to provide history and context about the removal power in the country’s early years that also could lead the court to revise its views. “I’m not holding my breath,” she said.

Slaughter’s lawyers embrace the historians’ arguments, telling the court that limits on Trump’s power are consistent with the Constitution and U.S. history.

The Justice Department argues Trump can fire board members for any reason as he works to carry out his agenda and that the precedent should be tossed aside.

“Humphrey’s Executor was always egregiously wrong,” Solicitor General D. John Sauer wrote.

A second question in the case could affect Cook, the Fed governor. Even if a firing turns out to be illegal, the court wants to decide whether judges have the power to reinstate someone.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote earlier this year that fired employees who win in court can likely get back pay, but not reinstatement.

That might affect Cook’s ability to remain in her job. The justices have seemed wary about the economic uncertainty that might result if Trump can fire the leaders of the central bank. The court will hear separate arguments in January about whether Cook can remain in her job as her court case challenging her firing proceeds.

The Dictatorship

White House hall of shame targets news outlets

NEW YORK (AP) — President Donald Trump’s White House is taking on the role of media critic and asking for help from “everyday Americans.”

The White House launched a web portal it says will spotlight bias on the part of news outlets, targeting the Boston Globe, CBS News, The Independent and The Washington Post in its first two “media offenders of the week.”

It’s the latest wrinkle in the fight against what Trump, back in his first term, labeled “fake news.” The Republican president has taken outlets like CBS News and The Wall Street Journal to court over their coverage, is fighting The Associated Press in court over media access and has moved to dismantle government-run outlets like Voice of America.

Trump has also engaged in personal attacks, last month alone saying “quiet, piggy,” to a female reporter who was questioning him on Air Force One, calling a reporter from The New York Times “ugly, both inside and out” and publicly telling an ABC News journalist she was “a terrible reporter.”

“It’s honestly overwhelming to keep up with it all and to constantly have to defend against this fake news and these attacks,” said press secretary Karoline Leavitt, who called the new web portal an attempt to hold journalists accountable.

After its debut, the White House asked for volunteers to submit their own examples of media bias. “So-called ‘journalists’ have made it impossible to identify every false or misleading story, which is why help from the American people is essential,” Trump’s press office said.

Devouring the media like hot french fries

Despite the attacks, Axios wrote this week that the mainstream media is ending the year as “dominant as ever” in capturing the president’s attention and setting Washington’s agenda, citing as one example The Washington Post’s reporting on military strikes against boats with alleged drug smugglers.

The irony is that Trump engages with reporters at a level he hasn’t seen with any other president in his lifetime, said Axios CEO Jim VandeHei, co-author of the report with Mike Allen.

“He’s always bitched about the media and the press,” VandeHei told The Associated Press. “He gobbles this stuff up like hot McDonald’s french fries. He’s a mass consumer of this. He watches it, he calls reporters, he takes calls from reporters. … That’s always been the contradiction with him.”

CBS, the Globe and The Independent were criticized for stories about Trump’s reaction to Democratic lawmakers who recorded a video reminding military members they were not required to follow unlawful orders. Trump accused the lawmakers of sedition “punishable by death.”

The White House said it was a misrepresentation to say Trump had called for their executions. The portal also said news outlets “subversively implied” that the president had issued illegal orders. The news articles they cited did not specifically say whether Trump had or had not ordered illegal activities.

Leavitt has been sharply critical of the Post’s story on Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s role in attacks on boats used by alleged drug smugglers in Central America. The portal this week accused the newspaper of trying to undermine anti-terrorist operations.

“Let’s be clear what’s happening here: the wrongful and intentional targeting of journalists by government officials for exercising a constitutionally protected right,” said the Post’s executive editor, Matt Murray. “The Washington Post will not be dissuaded and will continue to report rigorously and accurately in service to all of America.”

The new portal also contains an “Offender Hall of Shame” of articles it deems unfair and a leaderboard ranking outlets with the most pieces it objects to. Twenty-three outlets are represented, led by the Post’s six stories. CBS News, The New York Times and MS NOW, the network formerly known as BLN, had five apiece. No news outlets that appeal to conservatives were cited for bias.

Media watchdog welcomes the company

The conservative media watchdog Media Research Center, which has accused news outlets of having a liberal bias since 1987, welcomes the company.

“We’re pleased,” said Tim Graham, MRC’s director of media analysis. “It’s a stronger effort than Republican presidents have done before. I think all Republicans realize today that the media is on the other side and need to be identified as on the other side.”

VandeHei said about the portal, “I can’t think of anything I care less about. If they want to set up a site and point out bias, great. It’s called free speech. Do it. I don’t think it makes a damned bit of difference.”

What is damaging, VandeHei said, is a constant drumbeat of claims that what people read in the media is false. “It makes people suspicious of the truth and the country suffers when we’re not operating from some semblance of a common truth,” he said.

___

David Bauder writes about the intersection of media and entertainment for the AP. Follow him at http://x.com/dbauder and https://bsky.app/profile/dbauder.bsky.social.

The Dictatorship

Trump administration fails in latest bid to halt grants for school mental health workers

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — A federal appeals court on Thursday rejected the Trump administration’s bid to halt an order requiring it to release millions of dollars in grants meant to address the shortage of mental health workers in schools.

The mental health program, which was funded by Congress after the 2022 school shooting in Uvalde, Texasincluded grants meant to help schools hire more counselors, psychologists and social workers, with a focus on rural and underserved areas of the country. But President Donald Trump’s administration opposed aspects of the grant programs that touched on race, saying they were harmful to students and told recipients they wouldn’t receive funding past December 2025.

U.S. District Judge Kymberly K. Evanson, ruled in October that the administration’s move to cancel school mental health grants was arbitrary and capricious.

The U.S. Department of Education and Secretary of Education Linda McMahon requested an emergency stay and on Thursday, a panel from the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied that motion.

The panel wrote in its decision that the government hadn’t shown it is likely to succeed based on its claims that the district court doesn’t have jurisdiction or that it will be “irreparably injured absent a stay.”

The grants were first awarded under Democratic President Joe Biden’s administration. The Education Department prioritized giving the money to applicants who showed how they would increase the number of counselors from diverse backgrounds or from communities directly served by the school district.

Stay up to date with the news and the best of AP by following our WhatsApp channel.

The Trump administration said in a statement after the ruling in October that the grants were used “to promote divisive ideologies based on race and sex.”

The preliminary ruling by Evanson, a U.S. District Court judge in Seattle, applies only to some grantees in the 16 Democratic-led states that challenged the Education Department’s decision. In Madera County, California, for example, the ruling restores roughly $3.8 million. In Marin County, California, it restores $8 million.

-

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoFormer ‘Squad’ members launching ‘Bowman and Bush’ YouTube show

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Bob Good to step down as Freedom Caucus chair this week

-

The Dictatorship10 months ago

The Dictatorship10 months agoPete Hegseth’s tenure at the Pentagon goes from bad to worse

-

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoBlue Light News’s Editorial Director Ryan Hutchins speaks at Blue Light News’s 2025 Governors Summit

-

The Dictatorship10 months ago

The Dictatorship10 months agoLuigi Mangione acknowledges public support in first official statement since arrest

-

The Josh Fourrier Show1 year ago

The Josh Fourrier Show1 year agoDOOMSDAY: Trump won, now what?

-

Politics8 months ago

Politics8 months agoDemocrat challenging Joni Ernst: I want to ‘tear down’ party, ‘build it back up’

-

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoFormer Kentucky AG Daniel Cameron launches Senate bid