Politics

What 7 political experts will be watching at Tuesday’s debate

The debate Tuesday between Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris will be one to watch: the first time the two personally meet and the first time they’ll face off.

But what should you watch for?

We asked seven BLN analysts to weigh in on what they’ll be looking for during the first presidential debate between Harris and Trump. Here’s what they said.

Follow live updates on the Trump-Harris debate.

Steve Benen

When Trump takes the stage, he won’t have one opponent; he’ll have two. The first, obviously, will be Harris. The second will be himself. What I’ll be watching is whether the Republican nominee — who’s long struggled to maintain his composure while targeting women, especially women of color — has the discipline, decency and common sense to strike a presidential tone, treat the Democratic nominee with a modicum of respect and avoid the temptation to throw a tantrum that could cost him dearly. If recent history is any guide, even his most optimistic supporters should probably keep expectations low.

Brendan Buck

Harris has worked hard to present herself as the challenger in this race, but Trump has figured out a retort that is difficult for the vice president to answer: “Why didn’t you do it?” She will need a good explanation for why she now will be able to solve problems that she hasn’t while in the White House.

Brian Tyler Cohen

Will Harris be able to bait Trump into descending into one of his unhinged tirades and, if so, what should that tell us about the ease with which Trump can be manipulated (and what are the national security implications that come with it)? Will Trump be able to control himself when challenged by not just a Black woman — but the one who replaced his dream opponent — Joe Biden — on which Trump’s entire campaign was built?

Susan Del Percio

Watch how Harris uses her time. With muted microphones, time management will be essential. Trump rambles, often unable to deliver a clear, coherent response to just about any question. Harris will watch the clock and make her point — although she may sound a little over-rehearsed — and still leave time to get under Trump’s skin. She wins.

Voters want to know more about Harris. She must share her biography, accomplishments and plans for her presidency.

Alicia Menendez

Persuadable voters are the key audience. They may not watch the debate in real time, but they will catch key moments in clips. For those voters,new informationis what will move their candidate preference. Voters want to know more about Harris. She must share her biography, accomplishments and plans for her presidency, specifically around her opportunity agenda. Moreover, she must not only remind voters what Trump did during his first term, but connect those actions tofutureactions.

Michael Steele

I wrote about this for the BLN Daily newsletter on Friday. I want to see if Harris can thread the needle between appearing prosecutorial and being presidential. When she’s on the stage with a pathological liar, her instinct will be to correct him and throw facts back. That might work to a degree and at specific times, but the trap is to remember she’s not running for California attorney general; she’s running for president of the United States.

Charlie Sykes

Because Biden’s debate performance was so historically disastrous, people forget how genuinely awful Trump was. He lied incessantly, blustered and got lost in his own gibberish. If anything, he’s gotten worse since then; and now he faces a far more formidable opponent in Harris. This is her challenge: she has to be the grown-up in the room while calling out his lies, his threats, and his insults — without being dragged down into the Trumpian muck. If she does, she will have turned the corner in the race.

Ryan Teague Beckwith is a newsletter editor for BLN. He has previously worked for such outlets as Time magazine, Bloomberg News and CQ Roll Call. He teaches journalism at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies.

Politics

Serious investigation or ‘clown show’? Clintons’ closed testimonies on Epstein leave room for disagreement

Democrats say the depositions pave the way for slapping Trump with a subpoena. Republicans say they point to his exoneration…

Read More

Politics

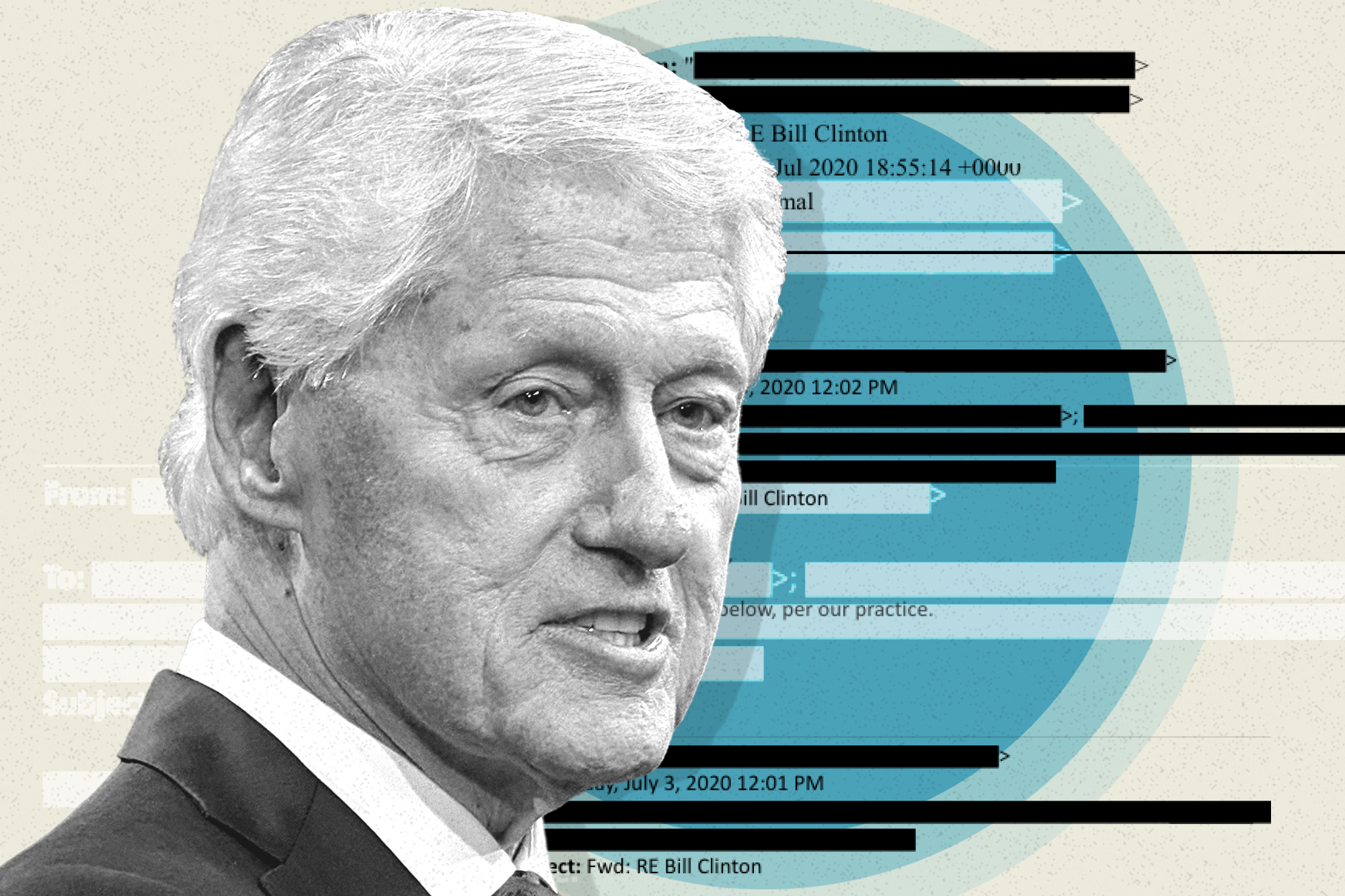

House Oversight chair: Bill Clinton punts question to committee on whether Trump should testify in Epstein probe

Former President Bill Clinton told members of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee that it’s “for you to decide” whether to call up current President Donald Trump to testify in the panel’s Jeffrey Epstein investigation, Chair James Comer told reporters Friday. “[He] went on to say that…

Read More

Politics

FEMA taps billions for disasters, warning Democrats of ‘dire’ shutdown impact

The Trump administration spent more than half of the balance in the nation’s disaster relief fund this week, pointing to that dwindling aid as means to pressure Democrats into yielding in Department of Homeland Security funding negotiations. A FEMA spokesperson said Friday that the agency sent out more than $5 billion this week for recovery projects…

Read More

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoLuigi Mangione acknowledges public support in first official statement since arrest

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer ‘Squad’ members launching ‘Bowman and Bush’ YouTube show

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoBlue Light News’s Editorial Director Ryan Hutchins speaks at Blue Light News’s 2025 Governors Summit

-

The Dictatorship6 months ago

The Dictatorship6 months agoMike Johnson sums up the GOP’s arrogant position on military occupation with two words

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer Kentucky AG Daniel Cameron launches Senate bid

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoPete Hegseth’s tenure at the Pentagon goes from bad to worse

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Bob Good to step down as Freedom Caucus chair this week

-

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoDemocrat challenging Joni Ernst: I want to ‘tear down’ party, ‘build it back up’