The Dictatorship

Australia’s hate speech crackdown is a threat to legitimate dissent

The Bondi Beach massacre of Dec. 14, in which 15 people were murdered during a Hanukkah celebration, has become a grim symbol of rising antisemitic violence across Western democracies. In Sydney, as well as in places like Paris, London, Berlin and Copenhagen, Jews have been living in fear of threats, intimidation and terrorist violence.

Governments have rushed to act. Too often, however, their response has been to expand laws criminalizing speech — an approach that offers the appearance of resolve while doing little to address the sources of violence and much to erode fundamental freedoms. Australia offers a telling example.

Following outbreaks of antisemitism after Hamas’ attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, Australian hate speech laws were expanded both at the federal level and in New South Waleswhere Bondi Beach is located. As became all too clear on Dec. 14, these laws did nothing to prevent the attack.

What began as a moment of national mourning has rapidly turned into one of the most sweeping expansions of hate speech laws and protest restriction powers in the country’s modern history.

Yet, the immediate response of Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese has been to promise yet more speech-restrictive legislation. What began as a moment of national mourning has rapidly turned into one of the most sweeping expansions of hate speech laws and protest restriction powers in the country’s modern history. Intended as an urgent response to antisemitism, new federal and state measures threaten to reach far beyond violence or direct incitement — reshaping how speech, protest and political dissent are regulated in the wake of terrorism.

The Bondi Beach attack has also had ramifications for free speech outside Australia. British police arrested two people after announcing their intentions to crack down on the pro-Palestinian slogans “globalize the intifada” and “from the river to the sea.” This policy has already been introduced in Germany, with ramifications for protest and online dissent.

There’s no doubt these slogans are deeply offensive to many Jews, who reasonably hear them as legitimizing violence. But when the government criminalizes speech that is merely offensive and ambiguous, rather than incitement to imminent violence, there are serious second-order consequences. The freedom to dissent and protest is the most fundamental difference between democracies and authoritarian states. The vagueness of hate speech laws risks blurring that bright line. Moreover, the very minorities that hate speech laws are supposed to protect can easily become their targets.

In Germany, the Israeli-Jewish left-wing activist Iris Hefets has been detained by police on several occasions for solo protests carrying a placard with the words “As a Jew and Israeli, stop the genocide in Gaza.” One does not have to agree with Hefets’ views on the Gaza conflict to see that arresting her for using politically charged language constitutes a threat to peaceful political protest. In fact, to suppress illegal chants, slogans and symbols, police in Berlin went so far as to ban all protests in languages other than German or Englishunless a “police-approved” interpreter was present.

Predictably, the policy backfired spectacularly. In July 2024, police intervened during a pro-Ukrainian demonstration outside the Russian Embassy in Berlin, where Ukrainian speakers protested a Russian airstrike on a children’s hospital in Kyiv.

Hate speech laws can also end up protecting those in power against criticism. In 2024, Marieha Hussain, a British teacher of South Asian heritage, attended a pro-Palestinian demonstration in London and carried a placard caricaturing then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and then-Home Secretary Suella Braverman as “coconuts.” Hussain was charged with a racially aggravated public order offense. After losing her job, being doxed and standing trial while nine months pregnant, Hussain was acquittedbut only because the judge found that the context placed the placard within political satire rather than criminal abuse.

This instinct to suppress speech in the name of protection is not new, but it sharply diverges from the way earlier generations of civil rights leaders confronted bigotry and helped shape the tradition of free speech exceptionalism, especially in America.

Historically, American Jewish organizations opposed hate speech laws. In the 1930s, as states and municipalities sought to criminalize the rhetoric of American Nazi groups, the American Jewish Committee formally rejected such measures, arguing that they would hurt minorities. Vague laws criminalizing the expression of racial or religious “hatred” or “offense” could be turned against minority groups, who could be accused of “hatred” when speaking out against discrimination.

Black civil rights organizations came to the same realization. Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP opposed a Florida hate speech bill, observing that “there is grave danger that these bills when enacted will serve to throttle … any [speaker] which seeks to champion the cause of minority groups,” since “laws imposing penalties on expression of opinion usually defeat their own purpose.”

Hate speech laws can also end up protecting those in power against criticism.

In the wake of a series of temple bombings in the South in the 1950s, when segregationists targeted synagogues that promoted racial integration, several Jewish organizations insisted that counter-speech and education were more effective remedies for antisemitism than hate speech regulation.

Laws prohibiting hate speech would “at best control the symptoms but would not reach the disease,” observed the American Jewish Congress in a policy statement from 1958 titled “Bombings and Hate Sheets.” The American Jewish Congress’ support of the NAACP, which was being persecuted in the South for its civil rights organizing, made the organization acutely aware of the importance of freedom of speech to the pursuit of civil rights. In the 1960s, the NAACP went as far as to defend the free speech of white supremacists, knowing that the survival of the civil rights movement depended on a broad reading of freedom of speech.

Eighty years after the Holocaust, increasing antisemitism is a moral failure of Western democracies. But Jewish and Black civil rights leaders have understood that when fear drives democracies to suppress speech, the very freedoms that have allowed minorities to organize and demand equality are undermined.

Laws that promise safety by policing words may satisfy a public appetite for action, but they do not stop violence. What they do is corrode democratic culture and hand extremists the grievance they crave.

If liberal societies are serious about preventing hate crimes, they should resist the temptation to criminalize speech and instead recommit to the harder work of defending free expression, confronting violence directly and fighting hate crimes through law enforcement, education and solidarity — not censorship.

Jacob Mchangama

Jacob Mchangama is the executive director of The Future of Free Speech and a research professor at Vanderbilt University. He is also the author of “Free Speech: A History From Socrates to Social Media.”

Professor of law at the University of Iowa College of Law

The Dictatorship

TENSIONS FLARE ON HILL

WASHINGTON (AP) — Tensions flared as questions mounted at the U.S. Capitol on Tuesday over the Trump administration’s shifting rationale for war with Iran as lawmakers demand answers over the strategy, exit plan and costs to Americans in lives and dollars for what is quickly becoming a widening Middle East conflict.

Trump officials made their case at the Capitol during a second day of closed-door briefings, this time with all members of the House and Senate ahead of a looming war powers resolution vote intended to restrict Trump’s ability to continue the joint U.S.-Israel campaign against Iran.

“The president determined we were not going to get hit first. It’s that simple,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in a testy exchange with reporters at the Capitol.

Rubio pushed back on his own suggestion a day earlier that Trump decided to strike Iran because Israel was ready to act first. Instead, he said Trump made the decision to attack this past weekend because it presented a unique opportunity with maximum chance for success.

“There is no way in the world that this terroristic regime was going to get nuclear weapons, not under Donald Trump’s watch,” he said.

The sudden pivot to a U.S. wartime footing has disrupted the political and policy agenda on Capitol Hill and raised uneasy questions about the risks ahead for a prolonged conflict and regime change after the killing of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. At least six U.S. military service personnel have died so far.

The situation has intensified the push in Congress for the war powers resolution — among the most consequential votes a lawmaker can take, with the war well underway — as administration officials are telling lawmakers they will likely need supplemental funds to pay for the conflict. It comes at the start of a highly competitive midterm election season that will test Trump’s slim GOP control of Congress.

Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer left the closed hearing, saying he was concerned about “mission creep” in a long war.

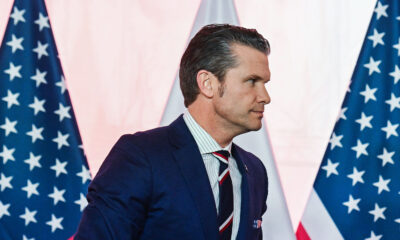

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senators demand answers, and some cheer Trump on

Senators spent the morning grilling Trump officials during an Armed Services Committee hearing over Rubio’s claim Monday that the president, believing that Israel was ready to act, decided it was better for the U.S. to launch a preemptive strike to prevent Iran’s potential retaliation on American military bases and interests abroad.

Sen. Angus King, the independent from Maine, said it’s “very disturbing” that Trump took the U.S. to war because Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wanted to bomb Iran. Past U.S. presidents, he said, “have consistently said, ‘No.’”

Defense official Elbridge Colby told senators the president directed the military campaign to destroy Iranian missiles and deny the country nuclear weapons.

Trump himself disputed the idea that Israel had forced his hand. In his own Oval Office remarks, he said, “I might might have forced their hand.”

Sen. Markwayne Mullin, a Trump ally from Oklahoma, said the president “did the world a favor.”

“How about we say, ‘Thank you, Mr. President, for finally getting rid of this nuisance,’” he said.

But Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., demanded to know how this fits into Trump’s “America First” campaign promise not to commit U.S. troops to protracted military campaigns abroad.

Trump has suggested the war could drag on, and has not ruled out sending American troops into Iran.

“’America First’ and ‘peace through strength’ are served by rolling back — as the military campaign is designed to do — the threats posed,” Colby responded. “This is certainly not nation-building. This is not going to be endless.”

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., arrives for a briefing for Senators on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Intelligence Committee Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., speaks to reporters following a House and Senate Intelligence Committees briefing about the war in Iran at the Capitol in Washington, Monday, March 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

What’s next for the Iranian regime and its people

Questions are growing over who will lead Iran after the death of Khamenei, who has ruled the country for decades, and worries of a leadership vacuum that creates unrest.

Democrats warned against sending U.S. military troops into Iran after more than two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

“I am more fearful than ever we may be putting boots on the ground,” said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., after the closed briefing.

And while House Republicans applauded in support of the Trump administration’s operations, warning signs flared.

Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, said he supports the operation, for now. “My flag starts going up, the longer this goes, my flag starts going up, the more there’s boots on the ground,” he said.

Many lawmakers expressed concern over the number of Americans calling their offices seeking help evacuating from the region as the war spreads. “It’s getting worse, not better,” said Rep. Jason Crow, D-Colo., a former Army Ranger.

Trump, in calling for Iranians to seize this opportunity to take back their country, has acknowledged the uncertainty.

“Most of the people we had in mind are dead,” Trump said Tuesday. He also panned the idea of elevating Reza Pahlavi, the exiled crown prince of Iran’s last shah, to take over in Iran.

Republicans insist it’s not for the Americans to decide the future of Iran.

“That’s going to be largely up to the Iranian people,” said Senate Majority Leader John Thune, a Republican.

House Speaker Mike Johnson said flatly, “We have no ability to get into the nation-building business.”

President Donald Trump departs after a Medal of Honor ceremony in the East Room of the White House, Monday, March 2, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President Donald Trump departs after a Medal of Honor ceremony in the East Room of the White House, Monday, March 2, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

War powers resolutions become a consequential vote

Both the House and Senate are preparing to vote on war powers resolutions that would restrain Trump’s ability to continue waging war on Iran without approval from Congress.

Under the U.S. Constitution, it’s up to Congress, not the president, to decide when the country goes to war. But lawmakers often shirk that duty, enabling the executive branch to amass more power to send the military into combat without congressional approval.

“Why are we spending billions of dollars to bomb Iran?” said House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries, who said there would be strong support from Democrats for the resolution.

But Johnson has said it would be “frightening” and “dangerous” to tie the president’s hands at this time, when the U.S. is already engaged in combat.

Other lawmakers have suggested that if Congress does not vote to restrain Trump, it should next consider an Authorization of the Use of Military Force, which would require lawmakers to go on record with affirmative support for the Iran operation.

“The reason why there’s so much consternation on our side is because President Trump has not given us a clear reason why he is in Iran,” said Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y. “If he wants to declare war on Iran, that is the job and responsibility of Congress under the Constitution.”

Former President George W. Bush sought, and received, authorization from Congress to launch the post-9/11 wars.

___

Associated Press writers Stephen Groves and Mary Clare Jalonick contributed to this report.

The Dictatorship

Trump threatens to cut off trade with Spain

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump on Tuesday threatened to end trade with Spainciting a lack of support over the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and the European nation’s resistance to increasing its NATO spending.

“We’re going to cut off all trade with Spain,” Trump told reporters during an Oval Office meeting with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz. “We don’t want anything to do with Spain.”

The U.S. president’s comments came a day after Spanish Foreign Minister José Manuel Albares said his country would not allow the U.S. to use jointly operated bases in southern Spain in any strikes not covered by the United Nations’ charter. Albares noted that the military bases in Spain were not used in the weekend attack on Iran.

Trump said despite Spain’s refusal “we could use their base if we want. We could just fly in and use it. Nobody’s going to tell us not to use it, but we don’t have to.”

It is unclear how Trump would cut off trade with Spain, given that Spain is under the umbrella of the European Union. The EU negotiates trade deals on behalf of all 27 member countries.

“If the U.S. administration wishes to review the trade agreement, it must do so respecting the autonomy of private companies, international law, and bilateral agreements between the European Union and the United States,” a spokesperson from Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s office said Tuesday.

The EU said it expects the Trump administration to honor a trade deal struck with the 27-nation bloc in Scotland last year after months of economic uncertainty over Trump’s tariff blitzkrieg.

“The Commission will always ensure that the interests of the European Union are fully protected,” said European Commission spokesperson Olof Gill.

It was just the latest instance of the president wielding the threat of tariffs or trade embargoes as a punishment and came on the heels of a Supreme Court decision that struck down Trump’s far-reaching global tariffs. While the court said that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act does not authorize the president to unilaterally impose sweeping tariffs, Trump now maintains that the court allows him to instead impose full-scale embargoes on other nations of his choosing.

Trump also complained anew Tuesday about Spain’s decision last year to back out of NATO’s 5% defense spending target. At the time, Spain said it could reach its military capabilities by spending 2.1% of its GDP, a move that Trump roundly criticized and responded to with tariff threats as well.

Spain, Trump said, is “the only country that in NATO would not agree to go up to 5%” in NATO spending. “I don’t think they agreed to go up to anything. They wanted to keep it at 2% and they don’t pay the 2%.”

Merz noted that Trump was correct and said, “We are trying to convince them that this is a part of our common security, that we all have to comply with this.”

Spain defended its position Tuesday, saying it is “a key member of NATO, fulfilling its commitments and making a significant contribution to the defense of European territory,” the spokesperson in Sánchez’s office said.

During the Oval Office meeting, Trump turned to U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent for his opinion on the president’s embargo authority.

Bessent said, “I agree that the Supreme Court reaffirmed your ability to implement an embargo.” Bessent added that the U.S. Trade Representative and Commerce Department would “begin investigations and we’ll move forward with those.”

A representative from the U.S. Treasury Department did not respond to a request from The Associated Press for additional comment.

Sánchez has been critical of the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran, calling it an “unjustifiable” and “dangerous” military intervention. His government has demanded an immediate de-escalation and dialogue and also condemned Iran’s strikes across the region.

Trump said, “Spain has absolutely nothing that we need other than great people. They have great people, but they don’t have great leadership.”

Spain’s position on the use of U.S. bases in its territory marks the latest flare-up in its relationship with the Trump administration. Under Sánchez, Europe’s last major progressive leader, Spain was also an outspoken critic of Israel’s war in Gaza.

___

Naishadham reported from Madrid. AP journalist Sam McNeil in Brussels contributed.

The Dictatorship

The Latest: US and Israel attack Iran as Trump says US begins ‘major combat operations’

Rice secures 80-74 win over Temple

Anthony’s 16 help Iona beat Manhattan 69-65

Folefac scores 23 as Siena beats Rider 76-61

SnoCountry Mountain Reports

Gulf States Sportswatch Daily Listings

Quinnipiac wins 67-63 against Canisius

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoLuigi Mangione acknowledges public support in first official statement since arrest

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer ‘Squad’ members launching ‘Bowman and Bush’ YouTube show

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoBlue Light News’s Editorial Director Ryan Hutchins speaks at Blue Light News’s 2025 Governors Summit

-

The Dictatorship6 months ago

The Dictatorship6 months agoMike Johnson sums up the GOP’s arrogant position on military occupation with two words

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer Kentucky AG Daniel Cameron launches Senate bid

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoPete Hegseth’s tenure at the Pentagon goes from bad to worse

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Bob Good to step down as Freedom Caucus chair this week

-

Politics11 months ago

Politics11 months agoDemocrat challenging Joni Ernst: I want to ‘tear down’ party, ‘build it back up’