The Dictatorship

Trump’s education cuts: What happens when rural schools lose money

SHELBYVILLE, Ky. (AP) — When the funding for Shannon Johnson’s job as a school mental health counselor came to an abrupt end, two years into a five-year grant, she thought about the work left to be done.

Johnson taught elementary and middle-school students in rural Kentucky how to navigate conflict, build resilience and manage stress and anxiety before a crisis happens. Few districts, especially rural ones, can dedicate a full-time role to early intervention amid a national shortage of mental health staff.

But the Trump administration discontinued her grantgiving her a sudden end date. So when another job opened in Shelby County Public Schools — this one not reliant on federal grants — she took it.

The district 30 miles east of Louisville does not plan to fill her former position. Without the federal money, it cannot.

Federal dollars make up roughly 10% of education spending nationally, but the percentage is significantly higher in rural districts, which are not able to raise as much money on property taxes.

When the funding is reduced, many districts have no way to make up the lost money.

Since President Donald Trump’s administration began its sweeping examination of federal grants to schools and universities, millions of dollars for programs supporting mental health, academic enrichment and teacher development have been withheld or discontinued. The Republican administration says the grants do not focus on academics and they prop up diversity or inclusion efforts that run counter to White House priorities.

Some grant cancellations have been temporarily paused during legal challenges. But for schools whose states are not fighting Washington’s decisions, there is little relief to be found.

That is the case in Kentucky. Nine rural school districts that received grants to hire counselors will have to decide whether they can afford to keep them. Already, more than half those counselors have left for other jobs.

To keep jobs supported by lost grants, schools must make other cuts

Federal money supports school programs for the most disadvantaged students, such as those with disabilities, kids learning the English language and children living in poverty. Some is appropriated by Congress for bipartisan priorities such as reducing barriers to education and improving youth mental health.

In Shelby County, where federal spending makes up about 18% of schools’ budgets, it also helps pay for teacher development opportunities — a key to staff retention — plus expanded after-school offerings that include tutoring, clubs and transportation.

The programs are not political, Superintendent Joshua Matthews said, and the funding loss only hurts students.

“I don’t know about everywhere in the country,” Matthews said. “But I can tell you in Shelby County, our teachers show up every day to make for sure that our kids are well taken care of, and we’re not promoting anything one way or the other.”

Even current levels of funding sometimes do not feel like enough, Matthews said. The district could try to use state or local money to help sustain the programs, but at the cost of paying for field trips or keeping class sizes small, he said.

For the counselors leaving districts that cannot afford to extend their positions, their youth mental health work is left unfinished.

“We had our minds and our goals and our plans really prepped for five-year work,” Johnson said. “We can’t really see a lot of change through systems in a year.”

The deep uncertainty has required educators to be prepared for an abrupt halt to their work while they look for ways to keep momentum, said Brigitte Blom, president and CEO of the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, which administers a federal grant for Shelby County and other school systems in Kentucky to expand engagement with the community and families.

“We have encouraged them to think about sustainability two years sooner than we would have,” she said.

In December, Blom learned that the administration would discontinue the federal grant.

Rural schools have few other places to turn for help

In Washington County, a rural district south of Shelby County with roughly 1,800 students, the grant helped launch a mentoring program, a career exploration class and expanded after-school academics. Schools with those programs have seen reductions in absenteeismsaid Tracy Abell, the district’s community schools director.

As federal money begins to dwindle, the effects will not be immediate. Superintendent Robin Cochran said it may take years for districts to see the gaps that emerge from programs that end today. Eventually, rural schools run out of options.

When larger districts lose funding, they may need to scale back programs. “For us, it means that it goes away,” Cochran said.

Shelby County has used funding from the same federal grant to expand its community schools program, seeking out new partnerships with city government and local businesses for more classroom and after-school learning. In Simpsonville, when the city parks department noticed a shortage of fresh vegetables at its farmers market, the district saw an opportunity for Simpsonville Elementary School, just down the street.

There, students in Katie Strange’s class now learn about agriculture, biology and ecology by growing produce for the market. Strange incorporated the work of the garden — germination, planting and harvesting — into her lessons, while parents and community organizations volunteered supplies and time to build a set of garden beds, funded by the community schools grant.

Although deer ate much of the lettuce, Strange said the school cafeteria was able to collect enough leafy greens to serve the students for lunch — a highlight for the kids. In November, long after the growing season had ended, members of the school’s garden club still spoke over each other with rushed excitement, recounting the harvest.

Fourth grader Stefan Viljoen explained how they treated the garden with deer repellent and listed out their crops.

“We grew cherry tomatoes, regular tomatoes,” he started to say.

“Cucumbers!” second grader Raylee Longacre interjected. “And we tried to make them into pickles.”

“They didn’t taste too good,” said Savannah Cull, a third grader.

Nate Jebsen, the district’s community schools director, said that without dedicated funding for a role like his, the work to pursue such partnerships would fall to administrators who are already stretched thin.

Schools see a difficult path to bringing back grant-funded staff

In Eminence Independent Schools, just north of Shelby County, Emily Kuhn hopes her district will be able to extend her role as a school counselor beyond the end of this school year, when the money for the position runs out. In her district, with two schools and just under 1,000 students, the grant-funded role came without the administrative tasks most counselors juggle and focused on working with students on their mental health and emotional skills.

“It takes more than one year to build that with people here, because they’re a very tight-knit, small community,” Kuhn said. “I’ve noticed a huge difference this year compared to last, of kids coming in and trusting me.”

The Ohio Valley Educational Cooperative, which manages the grant that funded Kuhn and Johnson’s jobs, unsuccessfully appealed the administration’s decision to discontinue the funding, said Jason Adkins, chief executive officer. The federal lawsuit filed to challenge the grant’s termination temporarily restored the fundingbut only for a subset of districts, not including those in Kentucky.

This fall, the U.S. Education Department announced it would seek new applicants for the school mental health grants it pulled back. The Ohio Valley cooperative reapplied but was not awarded the new grant, Adkins said. Even if the cooperative had won the money, that would not have helped the staff originally hired. The new guidance limits recipients to hiring school psychologists and not counselors.

In the initial grants, the organization focused on hiring counselors, in part because of a shortage of psychologists in rural areas, Adkins said. School psychologists require more training and are in high demand in larger, urban districts. The goal was to hire quickly and start boosting mental health support right away.

Even if there was the money to hire more psychologists, Adkins said, he was unsure whether there would be enough applicants to fill those roles.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

The Dictatorship

Congress taking first votes on Iran war as debate rages about US goals

WASHINGTON (AP) — Senate Republicans voted down an effort Wednesday to halt President Donald Trump’s war against Irandemonstrating early support for a conflict that has rapidly spread across the Middle East with no clear U.S. exit strategy.

The legislation, known as a war powers resolutionfailed on a 47-53 vote tally. The vote fell mostly along party lines, though Republican Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky voted in favor and Democratic Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania voted against.

The war powers resolution gave lawmakers an opportunity to demand congressional approval before any further attacks are carried out. The vote forced them to take a stand on a war shaping the fate of U.S. military members, countless other lives and the future of the region.

Underscoring the gravity of the moment, Democratic senators filled the Senate chamber and sat at their desks as the voting got underway. Typically, senators step into the chamber to cast their vote, then leave.

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., speaks to reporters during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, D-N.Y., speaks to reporters during a news conference on Capitol Hill in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

“Today every senator — every single one — will pick a side,” Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer said before the vote. “Do you stand with the American people who are exhausted with forever wars in the Middle East or stand with Donald Trump and Pete Hegseth as they bumble us headfirst into another war?”

Sen. John Barrasso, second in Senate Republican leadership, said during the debate that GOP senators were sending a message that Democrats are wrong for forcing a vote on the war powers resolution.

“Democrats would rather obstruct Donald Trump than obliterate Iran’s national nuclear program,” he added.

Trump administration scrambles for congressional support

AP AUDIO: Congress is taking its first votes on the Iran war as debate rages about US goals

AP Washington correspondent Sagar Meghani reports on Congress weighing in amid the war against Iran.

After launching a surprise attack against Iran on Saturday, Trump has scrambled to win support for a conflict that Americans of all political persuasions were already wary of entering. Trump administration officials have been a frequent presence on Capitol Hill this week as they try to reassure lawmakers that they have the situation under control.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said Wednesday that the war could extend eight weeks, a longer time frame than has previously been floated by the Trump administration. He also acknowledged that Iran is still able to carry out missile attacks even as the U.S. tries to control the country’s airspace.

U.S. service members “remain in harm’s way, and we must be clear-eyed that the risk is still high,” Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said at the same press conference.

Six U.S. military members were killed over the weekend in a drone strike in Kuwait.

Republican Sen. Joni Ernst of Iowa acknowledged the human costs of the war in her floor speech. Two of the soldiers killed Sunday were from Iowa and a National Guard unit from her state was also attacked in Syria in December, resulting in the deaths of two other soldiers.

“But now is our opportunity to bring an end to the decades of chaos,” said Ernst, who herself served as an officer in the Iowa National Guard for two decades.

“The sooner the better,” she added.

Trump has also not ruled out deploying U.S. ground troops. He has said he is hoping to end the bombing campaign within a few weeks, but his goals for the war have shifted from regime change to stopping Iran from developing nuclear capabilities to crippling its navy and missile programs.

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., center, joined at left by Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., the GOP whip, speaks to reporters at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., center, joined at left by Sen. John Barrasso, R-Wyo., the GOP whip, speaks to reporters at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

“We should be careful about opening a door into chaos in the Middle East when we cannot see the other side of it,” Democratic Sen. Chris Coons of Delaware said in a solemn floor speech after the vote concluded.

He said he was praying for “grace to find a path forward together where more do not needlessly join those who have already fallen in this new war in the Middle East.”

Lawmakers go on record

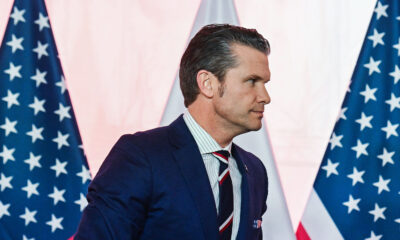

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

The votes in Congress this week represented potentially consequential markers of just where lawmakers stand on the war as they look ahead to midterm elections and the consequences of the conflict.

“Nobody gets to hide and give the president an easy pass or an end-run around the Constitution,” said Sen. Tim Kaine, the Virginia Democrat leading the war powers resolution.

Republican leaders have successfully, though narrowly, defeated a series of war powers resolutions pertaining to several other conflicts that Trump has entered or threatened to enter. This one, however, was different.

Unlike Trump’s military campaigns against alleged drug boats or even Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, the attack on Iran represents an open-ended conflict that is already ricocheting across the region. Several senators who have voted for previous war powers resolutions noted that they opposed this one because it applied to a conflict that is already raging.

“Passing this resolution now would send the wrong message to Iran and to our troops,” said GOP Sen. Susan Collins of Maine. “At this juncture, providing unequivocal support to our service members is critically important, as is ongoing consultation by the administration with Congress.”

House vote looms

On the other side of the Capitol, an intense debate over the war unfolded before a vote Thursday. The House first debated a resolution presented by GOP leadership affirming that Iran is the world’s largest state sponsor of terrorism.

Rep. Brian Mast, the GOP chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, publicly thanked Trump for taking action against Iran, saying the president is using his own constitutional authority to defend the U.S. against the “imminent threat” of Iran.

Mast, an Army veteran who worked as a bomb disposal expert in Afghanistan, said the Democratic resolution was effectively asking “that the president do nothing.”

Rep. Gregory Meeks, the top Democrat on the Foreign Affairs panel, said before the debate that the hardest votes he has taken in Congress have been to decide whether to send U.S. troops to war. “Our young men and women’s lives are on the line,” he said, his voice showing emotion as he emerged from a closed-door bri efing late Tuesday with Trump officials.

At a news conference Wednesday, several Democratic members who are also veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars spoke about the heavy costs of those conflicts.

One of them was Rep. Jason Crow, D-Colo. “I learned when I was fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, that when elites in Washington bang the war drums, pound their chest, talk about the costs of war and act tough, they’re not talking about them doing it, they’re not talking about their kids,” Crow said. “They’re talking about working class kids like us.”

The Dictatorship

TENSIONS FLARE ON HILL

WASHINGTON (AP) — Tensions flared as questions mounted at the U.S. Capitol on Tuesday over the Trump administration’s shifting rationale for war with Iran as lawmakers demand answers over the strategy, exit plan and costs to Americans in lives and dollars for what is quickly becoming a widening Middle East conflict.

Trump officials made their case at the Capitol during a second day of closed-door briefings, this time with all members of the House and Senate ahead of a looming war powers resolution vote intended to restrict Trump’s ability to continue the joint U.S.-Israel campaign against Iran.

“The president determined we were not going to get hit first. It’s that simple,” Secretary of State Marco Rubio said in a testy exchange with reporters at the Capitol.

Rubio pushed back on his own suggestion a day earlier that Trump decided to strike Iran because Israel was ready to act first. Instead, he said Trump made the decision to attack this past weekend because it presented a unique opportunity with maximum chance for success.

“There is no way in the world that this terroristic regime was going to get nuclear weapons, not under Donald Trump’s watch,” he said.

The sudden pivot to a U.S. wartime footing has disrupted the political and policy agenda on Capitol Hill and raised uneasy questions about the risks ahead for a prolonged conflict and regime change after the killing of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. At least six U.S. military service personnel have died so far.

The situation has intensified the push in Congress for the war powers resolution — among the most consequential votes a lawmaker can take, with the war well underway — as administration officials are telling lawmakers they will likely need supplemental funds to pay for the conflict. It comes at the start of a highly competitive midterm election season that will test Trump’s slim GOP control of Congress.

Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer left the closed hearing, saying he was concerned about “mission creep” in a long war.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth arrives for a briefing for lawmakers on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senators demand answers, and some cheer Trump on

Senators spent the morning grilling Trump officials during an Armed Services Committee hearing over Rubio’s claim Monday that the president, believing that Israel was ready to act, decided it was better for the U.S. to launch a preemptive strike to prevent Iran’s potential retaliation on American military bases and interests abroad.

Sen. Angus King, the independent from Maine, said it’s “very disturbing” that Trump took the U.S. to war because Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wanted to bomb Iran. Past U.S. presidents, he said, “have consistently said, ‘No.’”

Defense official Elbridge Colby told senators the president directed the military campaign to destroy Iranian missiles and deny the country nuclear weapons.

Trump himself disputed the idea that Israel had forced his hand. In his own Oval Office remarks, he said, “I might might have forced their hand.”

Sen. Markwayne Mullin, a Trump ally from Oklahoma, said the president “did the world a favor.”

“How about we say, ‘Thank you, Mr. President, for finally getting rid of this nuisance,’” he said.

But Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., demanded to know how this fits into Trump’s “America First” campaign promise not to commit U.S. troops to protracted military campaigns abroad.

Trump has suggested the war could drag on, and has not ruled out sending American troops into Iran.

“’America First’ and ‘peace through strength’ are served by rolling back — as the military campaign is designed to do — the threats posed,” Colby responded. “This is certainly not nation-building. This is not going to be endless.”

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, R-S.D., arrives for a briefing for Senators on Iran at a secure room in the basement of the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, March 3, 2026. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

Senate Intelligence Committee Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., speaks to reporters following a House and Senate Intelligence Committees briefing about the war in Iran at the Capitol in Washington, Monday, March 2, 2026. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)

What’s next for the Iranian regime and its people

Questions are growing over who will lead Iran after the death of Khamenei, who has ruled the country for decades, and worries of a leadership vacuum that creates unrest.

Democrats warned against sending U.S. military troops into Iran after more than two decades of war in Iraq and Afghanistan in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

“I am more fearful than ever we may be putting boots on the ground,” said Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., after the closed briefing.

And while House Republicans applauded in support of the Trump administration’s operations, warning signs flared.

Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, said he supports the operation, for now. “My flag starts going up, the longer this goes, my flag starts going up, the more there’s boots on the ground,” he said.

Many lawmakers expressed concern over the number of Americans calling their offices seeking help evacuating from the region as the war spreads. “It’s getting worse, not better,” said Rep. Jason Crow, D-Colo., a former Army Ranger.

Trump, in calling for Iranians to seize this opportunity to take back their country, has acknowledged the uncertainty.

“Most of the people we had in mind are dead,” Trump said Tuesday. He also panned the idea of elevating Reza Pahlavi, the exiled crown prince of Iran’s last shah, to take over in Iran.

Republicans insist it’s not for the Americans to decide the future of Iran.

“That’s going to be largely up to the Iranian people,” said Senate Majority Leader John Thune, a Republican.

House Speaker Mike Johnson said flatly, “We have no ability to get into the nation-building business.”

President Donald Trump departs after a Medal of Honor ceremony in the East Room of the White House, Monday, March 2, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

President Donald Trump departs after a Medal of Honor ceremony in the East Room of the White House, Monday, March 2, 2026, in Washington. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

War powers resolutions become a consequential vote

Both the House and Senate are preparing to vote on war powers resolutions that would restrain Trump’s ability to continue waging war on Iran without approval from Congress.

Under the U.S. Constitution, it’s up to Congress, not the president, to decide when the country goes to war. But lawmakers often shirk that duty, enabling the executive branch to amass more power to send the military into combat without congressional approval.

“Why are we spending billions of dollars to bomb Iran?” said House Democratic Leader Hakeem Jeffries, who said there would be strong support from Democrats for the resolution.

But Johnson has said it would be “frightening” and “dangerous” to tie the president’s hands at this time, when the U.S. is already engaged in combat.

Other lawmakers have suggested that if Congress does not vote to restrain Trump, it should next consider an Authorization of the Use of Military Force, which would require lawmakers to go on record with affirmative support for the Iran operation.

“The reason why there’s so much consternation on our side is because President Trump has not given us a clear reason why he is in Iran,” said Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y. “If he wants to declare war on Iran, that is the job and responsibility of Congress under the Constitution.”

Former President George W. Bush sought, and received, authorization from Congress to launch the post-9/11 wars.

___

Associated Press writers Stephen Groves and Mary Clare Jalonick contributed to this report.

The Dictatorship

Trump threatens to cut off trade with Spain

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump on Tuesday threatened to end trade with Spainciting a lack of support over the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran and the European nation’s resistance to increasing its NATO spending.

“We’re going to cut off all trade with Spain,” Trump told reporters during an Oval Office meeting with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz. “We don’t want anything to do with Spain.”

The U.S. president’s comments came a day after Spanish Foreign Minister José Manuel Albares said his country would not allow the U.S. to use jointly operated bases in southern Spain in any strikes not covered by the United Nations’ charter. Albares noted that the military bases in Spain were not used in the weekend attack on Iran.

Trump said despite Spain’s refusal “we could use their base if we want. We could just fly in and use it. Nobody’s going to tell us not to use it, but we don’t have to.”

It is unclear how Trump would cut off trade with Spain, given that Spain is under the umbrella of the European Union. The EU negotiates trade deals on behalf of all 27 member countries.

“If the U.S. administration wishes to review the trade agreement, it must do so respecting the autonomy of private companies, international law, and bilateral agreements between the European Union and the United States,” a spokesperson from Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s office said Tuesday.

The EU said it expects the Trump administration to honor a trade deal struck with the 27-nation bloc in Scotland last year after months of economic uncertainty over Trump’s tariff blitzkrieg.

“The Commission will always ensure that the interests of the European Union are fully protected,” said European Commission spokesperson Olof Gill.

It was just the latest instance of the president wielding the threat of tariffs or trade embargoes as a punishment and came on the heels of a Supreme Court decision that struck down Trump’s far-reaching global tariffs. While the court said that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act does not authorize the president to unilaterally impose sweeping tariffs, Trump now maintains that the court allows him to instead impose full-scale embargoes on other nations of his choosing.

Trump also complained anew Tuesday about Spain’s decision last year to back out of NATO’s 5% defense spending target. At the time, Spain said it could reach its military capabilities by spending 2.1% of its GDP, a move that Trump roundly criticized and responded to with tariff threats as well.

Spain, Trump said, is “the only country that in NATO would not agree to go up to 5%” in NATO spending. “I don’t think they agreed to go up to anything. They wanted to keep it at 2% and they don’t pay the 2%.”

Merz noted that Trump was correct and said, “We are trying to convince them that this is a part of our common security, that we all have to comply with this.”

Spain defended its position Tuesday, saying it is “a key member of NATO, fulfilling its commitments and making a significant contribution to the defense of European territory,” the spokesperson in Sánchez’s office said.

During the Oval Office meeting, Trump turned to U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent for his opinion on the president’s embargo authority.

Bessent said, “I agree that the Supreme Court reaffirmed your ability to implement an embargo.” Bessent added that the U.S. Trade Representative and Commerce Department would “begin investigations and we’ll move forward with those.”

A representative from the U.S. Treasury Department did not respond to a request from The Associated Press for additional comment.

Sánchez has been critical of the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran, calling it an “unjustifiable” and “dangerous” military intervention. His government has demanded an immediate de-escalation and dialogue and also condemned Iran’s strikes across the region.

Trump said, “Spain has absolutely nothing that we need other than great people. They have great people, but they don’t have great leadership.”

Spain’s position on the use of U.S. bases in its territory marks the latest flare-up in its relationship with the Trump administration. Under Sánchez, Europe’s last major progressive leader, Spain was also an outspoken critic of Israel’s war in Gaza.

___

Naishadham reported from Madrid. AP journalist Sam McNeil in Brussels contributed.

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoLuigi Mangione acknowledges public support in first official statement since arrest

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer ‘Squad’ members launching ‘Bowman and Bush’ YouTube show

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoBlue Light News’s Editorial Director Ryan Hutchins speaks at Blue Light News’s 2025 Governors Summit

-

The Dictatorship6 months ago

The Dictatorship6 months agoMike Johnson sums up the GOP’s arrogant position on military occupation with two words

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer Kentucky AG Daniel Cameron launches Senate bid

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoPete Hegseth’s tenure at the Pentagon goes from bad to worse

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Bob Good to step down as Freedom Caucus chair this week

-

Politics11 months ago

Politics11 months agoDemocrat challenging Joni Ernst: I want to ‘tear down’ party, ‘build it back up’