The Dictatorship

Palestinians fear a repeat of their 1948 mass expulsion in the wake of Trump’s remarks on Gaza

JERUSALEM (AP) — Palestinians will mark this year the 77th anniversary of their mass expulsion from what is now Israelan event that is at the core of their national struggle.

But in many ways, that experience pales in comparison to the calamity now faced in the Gaza Strip — particularly as President Donald Trump has suggested that displaced Palestinians in Gaza be permanently resettled outside the war-torn territory and that the United States take “ownership” of the enclave.

Palestinians refer to their 1948 expulsion as the Nakba, Arabic for catastrophe. Some 700,000 Palestinians — a majority of the prewar population — fled or were driven from their homes before and during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war that followed Israel’s establishment.

After the war, Israel refused to allow them to return because it would have resulted in a Palestinian majority within its borders. Instead, they became a seemingly permanent refugee community that now numbers some 6 million, with most living in slum-like urban refugee camps in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

In Gaza, the refugees and their descendants make up around three-quarters of the population.

Israel’s rejection of what Palestinians say is their right of return to their 1948 homes has been a core grievance in the conflict and was one of the thorniest issues in peace talks that last collapsed 15 years ago. The refugee camps have always been the main bastions of Palestinian militancy.

Now, many Palestinians fear a repeat of their painful history on an even more cataclysmic scale.

All across Gaza, Palestinians in recent days have been loading up cars and donkey carts or setting out on foot to visit their destroyed homes after a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war took hold Jan. 19. The images from several rounds of mass evacuations throughout the war — and their march back north on foot — are strikingly similar to black-and-white photographs from 1948.

Mustafa al-Gazzar, in his 80s, recalled in 2024 his family’s monthslong flight from their village in what is now central Israel to the southern city of Rafah, when he was 5. At one point they were bombed from the air, at another, they dug holes under a tree to sleep in for warmth.

Al-Gazzar, now a great-grandfather, was forced to flee again in the war, this time to a tent in Muwasi, a barren coastal area where some 450,000 Palestinians live in a squalid camp. He said then the conditions are worse than in 1948, when the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees was able to regularly provide food and other essentials.

“My hope in 1948 was to return, but my hope today is to survive,” he said.

The war in Gaza, which was triggered by Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack into Israel, has killed over 47,000 Palestinians, according to local health officials, making it by far the deadliest round of fighting in the history of the conflict. The initial Hamas attack killed some 1,200 Israelis.

The war has forced some 1.7 million Palestinians — around three quarters of the territory’s population — to flee their homes, often multiple times. That is well over twice the number that fled before and during the 1948 war.

Israel has sealed its border. Egypt has only allowed a small number of Palestinians to leave, in part because it fears a mass influx of Palestinians could generate another long-term refugee crisis.

The international community is strongly opposed to any mass expulsion of Palestinians from Gaza — an idea embraced by far-right members of the Israeli government, who refer to it as “voluntary emigration.”

Israel has long called for the refugees of 1948 to be absorbed into host countries, saying that calls for their return are unrealistic and would endanger its existence as a Jewish-majority state. It points to the hundreds of thousands of Jews who came to Israel from Arab countries during the turmoil following its establishment, though few of them want to return.

Even if Palestinians are not expelled from Gaza en masse, many fear that they will never be able to return to their homes or that the destruction wreaked on the territory will make it impossible to live there. One U.N. estimate said it would take until 2040 to rebuild destroyed homes.

The Jewish militias in the 1948 war with the armies of neighboring Arab nations were mainly armed with lighter weapons like rifles, machine guns and mortars. Hundreds of depopulated Palestinian villages were demolished after the war, while Israelis moved into Palestinian homes in Jerusalem, Jaffa and other cities.

In Gaza, Israel has unleashed one of the deadliest and most destructive military campaigns in recent history, at times dropping 2,000-pound (900-kilogram) bombs on dense, residential areas. Entire neighborhoods have been reduced to wastelands of rubble and plowed-up roads, many littered with unexploded bombs.

Yara Asi, a Palestinian assistant professor at the University of Central Florida who has done research on the damage to civilian infrastructure in the war, says it’s “extremely difficult” to imagine the kind of international effort that would be necessary to rebuild Gaza.

Even before the war, many Palestinians spoke of an ongoing Nakba, in which Israel gradually forces them out of Gaza, the West Bank and east Jerusalem, territories it captured during the 1967 war that the Palestinians want for a future state. They point to home demolitions, settlement construction and other discriminatory policies that long predate the war, and which major rights groups say amount to apartheidallegations Israel denies.

Asi and others fear that if another genuine Nakba occurs, it will be in the form of a gradual departure.

“It won’t be called forcible displacement in some cases. It will be called emigration, it will be called something else,” Asi said.

“But in essence, it is people who wish to stay, who have done everything in their power to stay for generations in impossible conditions, finally reaching a point where life is just not livable.”

___

Associated Press reporters Wafaa Shurafa and Mohammad Jahjouh in Rafah, Gaza Strip, contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press is republishing this story from May 14, 2024, to update with the ceasefire and President Donald Trump’s comments about the Gaza Strip.

The Dictatorship

MAGA world’s violent pregnancy-related rhetoric is on full display

Conservatives’ crusade against reproductive freedom is deathly serious. Two controversies over the past week highlight some of the violence undergirding the MAGA movement’s assault on the idea of people choosing when and whether to bear children.

In Tennessee, two GOP state lawmakers are gauging interest in legislation that would make people eligible for homicide charges — and potentially the death penalty — for receiving or assisting with an abortion.

The bill’s co-sponsor in the state Senate said he doesn’t think the bill currently has the votes but ultimately could. Per the WSMV television station in Nashville:

“We want to be very open and have a conversation, whether it’s controversial or not — let’s hear from all sides to see where we are as Tennessee and where we stand,”[stateSenMark[stateSenMark] Pody said. “Talking to some colleagues, we don’t have the votes to move something like that in the Senate at this moment.”

Pody said he does not consider the bill dead on arrival in the Senate, adding he believes there is a possibility for negotiation and that Republicans in the House and Senate could reach an agreement on language that could pass both chambers.

Most Americans seem to think we shouldn’t kick the tires on state-sponsored executions for abortion recipients. Pody apparently disagrees.

His fellow co-sponsor in the House, state Rep. Jody Barrett, didn’t sound any more sane in his exchanges about the bill with reporter Chris Davis from WTVF, the CBS affiliate in Nashville.

“Murder should be murder, whether it’s a person in being or a person in utero,” Barrett said.

I asked Barrett directly about the criticism that the bill unfairly targets mothers.

“I think that’s a talking point saying that you’re targeting mothers. We’re not targeting mothers. We’re targeting unborn children and trying to protect them and give them the protection under the law for you and me,” Barrett said.

The tacit admission came later:

“A simple examination of the death penalty in Tennessee would show that that’s just not realistic. Now, do I have to admit that the death penalty is a possibility? Sure. But since the death penalty was reinstated in Tennessee in 1977, there’s been less than 200 people sentenced to death, and only 16 have actually been executed — none of them women,” Barrett said.

It’s safe to say the latter remarks are probably not going to be enough to soothe concerns about this morbid proposal — one that mirrors several others across the country in the past year.

In Vermont, a different controversy is unfolding over a right-wing influencer named Hank Poitras, who was elected chairman of a county GOP committee — and who once delivered an extremely graphic diatribe about committing an act of violence on a woman’s womb after she got pregnant.

Ja’han Jones is an MS NOW opinion blogger. He previously wrote The ReidOut Blog.

The Dictatorship

Trump administration pauses Medicaid funding to Minnesota

The Trump administration is temporarily halting $259 million in Medicaid funding to Minnesota, Vice President JD Vance announced Wednesday.

Vance said the payments will be paused “until the state government takes its obligations seriously to stop the fraud that’s being perpetrated against the American taxpayer.”

The news of the temporary halting of the massive amount of federal funding — which provides health insurance to low-income people — comes as the state has been a target of the federal government following allegations of fraud perpetrated by child care providers in the state. In December, federal officials froze $185 million in child care funds to Minnesota, and last month, the administration announced it was freezing $10 billion in funding for social services programs in five Democratic-led states, including Minnesota.

The latest news also follows President Donald Trump’s announcement at the State of the Union address Tuesday night that he was tasking the vice president with waging a “war on fraud.”

Dr. Mehmet Oz, administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, said Wednesday that officials identified “scammers” who he claimed “hijacked … a certain part of the Minnesota Medicaid system.”

Federal prosecutors have confirmedthere was large-scale social services fraud in Minnesota, with dozensof people — many of whom are Somalis — having been convicted of stealing more than $1 billion in public funds intended for food, housing and services for people with disabilities. But the administration did not provide detailed evidence on Wednesday of the alleged large-scale Medicaid fraud in Minnesota that Oz claimed.

“These schemes disproportionately involve immigrant communities,” Oz said. Generally, undocumented people are not able to be enrolled in Medicaid.

Vance mentioned a program that he said claimed to offer after-school services to autistic children but did not actually do so, though he did not offer any identifying information.

Oz added that the top fraudulent biller in the state “submitted 450 days where they claim they were working more than 24 hours a day,” but also did not provide corroborating information.

According to the health policy research organization KFF, Medicaid covers nearly 1.2 millionkids and adults in Minnesota, more than half of whom are nursing home residents. More than three-quarters of Medicaid enrollees in the state are working full time, that data also shows.

Oz said the federal government will only release the funds “after they propose an act on a comprehensive corrective action plan to solve the problem,” adding that Gov. Tim Walz, D-Minn., has 60 days to do so. He suggested similar announcements to come in other states “soon,” and mentioned Florida, New York and California as potential future targets.

“This is not a problem with the people of Minnesota,” Oz said. “It’s a problem with the leadership of Minnesota and other states who do not take Medicaid preservation seriously.”

Vance added: “The main reason that we’re doing this is that we want to make sure that the people of Minnesota have access to the services that they’re entitled to.”

In a post on X on Wednesday night, Walz said the announcement “has nothing to do with fraud,” and added, “The agents Trump allegedly sent to investigate fraud are shooting protesters and arresting children. His DOJ is gutting the U.S. Attorney’s Office and crippling their ability to prosecute fraud. And every week, Trump pardons another fraudster.”

Minnesota lawmakers and the state’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, have introduced legislation that would add more than a dozen new staffers to the AG office’s Medicaid Fraud Control Unit and that would strengthen state fraud laws.

In a statement provided to MS NOW, Ellison hinted the state may sue in response.

“Courts have repeatedly found that their pattern of cutting first and asking questions later is illegal, and if the federal government is unlawfully withholding money meant for the 1.2 million low-income Minnesotans on Medicaid, we will see them in court,” he said.

Shireen Gandhi, commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Human Services, which administers Medicaid, said the government’s actions “significantly harm the state’s health care infrastructure and the 1.2 million Minnesotans who depend on Medicaid,” adding that federal officials “chose to ignore more than a year of serious and intensive work to fight fraud in our state.”

Spokespeople for Sen. Tina Smith, D-Minn., and Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., did not immediately respond to MS NOW’s request for comment.

Nour Longi and Emily Hung contributed reporting.

Julianne McShane is a breaking news reporter for MS NOW who also covers the politics of abortion and reproductive rights. You can send her tips from a non-work device on Signal at jmcshane.19 or follow her on X or Bluesky.

The Dictatorship

Trump says he’s ‘won affordability.’ The data shows a different story.

ByJosh Bivens

President Donald Trump has said some strikingly out-of-touch things about affordability: that it’s a “hoax,” he’s “solved it” and he’s “won affordability.” In his State of the Union address, he even said “prices are plummeting downward.” U.S. families know this is nonsense. But to see how much Trump’s policies will erode affordability in the coming years, you must understand that affordability isn’t just about prices.

Affordability is the outcome of a race between incomes and prices. And for typical families, the Trump agenda is near-guaranteed to harm their incomes far more than it can possibly reduce their prices.

For typical families, the Trump agenda is near-guaranteed to harm their incomes far more than it can possibly reduce their prices.

Even judged by the movement of prices alone, Trump’s record on affordability is poor. Inflation fell from 8.0% to 3.0% in the final two years of the Biden administration. This rapid downward movement slowed to a crawl in the first year of Trump’s second term, with inflation falling from 3.0% to just over 2.6%.

There are clear policy reasons why progress in reducing inflation has slowed. Electricity prices have surged as the Trump administration has ended subsidies for renewable generation passed during the Biden administration. The Trump tax cuts passed in the president’s first term were part of a law that gouged loopholes in the tax code, including inviting pharmaceutical companies to offshore their production and import back into the United States. Last year the Trump administration put tariffs on these offshored pharmaceuticals, pushing up their costs. When the administration failed to extend Obamacare subsidies for people buying health insurance through the exchanges, healthier enrollees who could afford to began opting out, driving up prices for everybody left in the Affordable Care Act marketplace.

And these are not the only ways that Trump administration policies have intensified affordability issues for ordinary Americans.

That failure to extend Obamacare subsidies did more than lead to higher market prices for exchange insurance plans. It also siphoned income away from families that could have been used to defray the cost of buying health insurance. Instead, out-of-pocket burdens spiked. Even bigger harm looms for more vulnerable families as the Republican tax and spending megabill, known as Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, is poised to cut Medicaid and food stamps by more than $1 trillion over the next decade. These cuts effectively remove income from the pockets of the most vulnerable. This explains why the bill reduced affordability for the bottom 40% of families in this country.

It is hard to make a bunch of changes to the nation’s tax and spending laws that add $4 trillion to the nation’s debt and still somehow manage to make 40% of the population worse off. If you’re borrowing it all anyhow, why not at least give something to the worst-off among us?

Finally, even as inflation fell slightly in 2025, wage growth adjusted for inflation (or real wages) also slowed. For the lowest-wage workers, these real wages actually declined. The reason is simple: The labor market cooled in 2025. This was no accident. The administration’s federal workforce cuts, deportation agenda and the chaos of the Trump tariff policy and approach to the Federal Reserve all contributed to labor market sluggishness. And workers in the bottom half of the wage distribution need sustained and very low unemployment rates to gain any leverage with employers when they ask for higher wages. They had this leverage early in the post-pandemic recovery, but it’s been lost. The labor market would have cooled even faster in 2025 had there not been a ramp-up in spending associated with the frenzied buildout of artificial intelligence firms and the related stock market boom (which could still prove to be a bubble).

With all that in mind about the scale of Trump policies’ negative impact on affordability, now let’s consider what genuine wins in affordability would look like.

A chief place to start: attacks on the influence that has most harmed U.S. families’ affordability in recent decades — the rise in inequality that has funneled income away from the bottom and middle toward the top. This expansion in inequality was policy-generatedso it can be reversed by different policy choices. Yet the Trump administration has doubled down on strategies that have increased inequality by hamstringing workers’ rights to organize unions and bargain collectively and rolling back important labor standards, such as minimum wages. (If you want more examples, my Economic Policy Institute colleagues and I identified 47 ways Trump has made life less affordable for Americans over the past year.)

The first step in a good-faith affordability agenda would be restoring the Medicaid and SNAP funds cut in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

The first step in a good-faith affordability agenda would be restoring the Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funds cut in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. The obvious way to pay for this restoration? By sharply raising taxes on the ultra-rich.

Besides being a key source of revenue to pay for affordability-enhancing measures such as Medicaid and food stamps, raising taxes on the ultra-rich would lower pre-tax inequality. Essentially, these higher taxes would blunt the incentive for the ultra-rich to rig the rules of the economy in order to claim as much income as they can at the expense of typical families. This strategy works — across time and across countries there is ample evidence that higher taxes on the rich keep pre-tax inequality in check.

The economic struggles of typical U.S. families deserve serious solutions, not political buzzwords. Unfortunately, the policies the Trump administration has undertaken are making Americans’ economic struggles harder, not easier.

Josh Bivens

Josh Bivens is the chief economist at the Economic Policy Institute.

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

The Dictatorship1 year agoLuigi Mangione acknowledges public support in first official statement since arrest

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer ‘Squad’ members launching ‘Bowman and Bush’ YouTube show

-

The Dictatorship6 months ago

The Dictatorship6 months agoMike Johnson sums up the GOP’s arrogant position on military occupation with two words

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoBlue Light News’s Editorial Director Ryan Hutchins speaks at Blue Light News’s 2025 Governors Summit

-

Politics1 year ago

Politics1 year agoFormer Kentucky AG Daniel Cameron launches Senate bid

-

The Dictatorship1 year ago

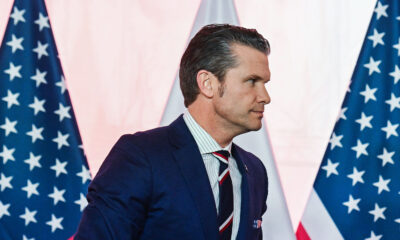

The Dictatorship1 year agoPete Hegseth’s tenure at the Pentagon goes from bad to worse

-

Uncategorized1 year ago

Bob Good to step down as Freedom Caucus chair this week

-

Politics10 months ago

Politics10 months agoDemocrat challenging Joni Ernst: I want to ‘tear down’ party, ‘build it back up’